What Are Springtails?

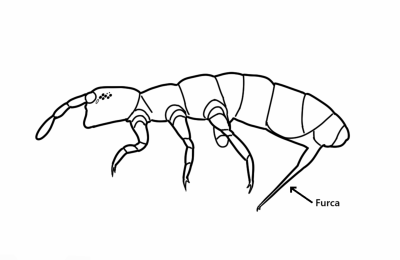

Springtails (Collembola) are small terrestrial invertebrates related to insects. They are, on average, about 1.5 mm long. They are wingless but possess a specialized structure called the furca, a jumping organ that allows them to leap up to 300 times their body length. Only the species adapted to underground life have lost this ability to jump.

Their diet varies depending on the species and habitat, but they primarily feed on organic detritus, microorganisms, algae, and fungi. Some springtail species live exclusively on glaciers and are commonly known as “glacier fleas”.

“Glacier Fleas”

In glacial environments—as in almost all terrestrial ecosystems—springtails are abundant and diversified. However, only a few species can be classified as glacier fleas: this term refers exclusively to those species that live in direct contact with the ice (ice-dwelling) and cannot survive outside the glacier environment. These species are typically darkly pigmented, often black, and are capable of forming dense populations on glacier surfaces. They should not be confused with other springtails that may form large aggregations on snow at lower elevations, below the tree line.

Glacier fleas are of particular conservation interest because they are the terrestrial animals in our regions most directly dependent on the existence of glaciers—and they are currently at risk of extinction due to global warming. First discovered in 1841, they remained largely unstudied until the CollembolICE research group began a dedicated investigation (see this scientific article for an initial overview of this diversity). Yet, much remains to be done to explore all glaciers.

CollembolICE focuses on these organisms to explore, monitor, and ultimately help conserve their biodiversity.

Collaboration is needed from everyone who cares about alpine biodiversity and ecology and who frequents glaciers—especially given the urgency imposed by climate change. The challenge is twofold: to discover what we still don’t know, and to protect what we can, before the ice—and the unique biodiversity it harbors—disappears forever.